I get a lot of questions about yin yoga, and it makes sense. The practice sits in a middle ground, asking students to stay still while wearing very different bodies, with varying injury histories and nervous system set points. Let’s separate myths from what research actually supports, and offer teachers practical ways to keep students safe while enjoying slow, connective-tissue-focused practice.

Short answer

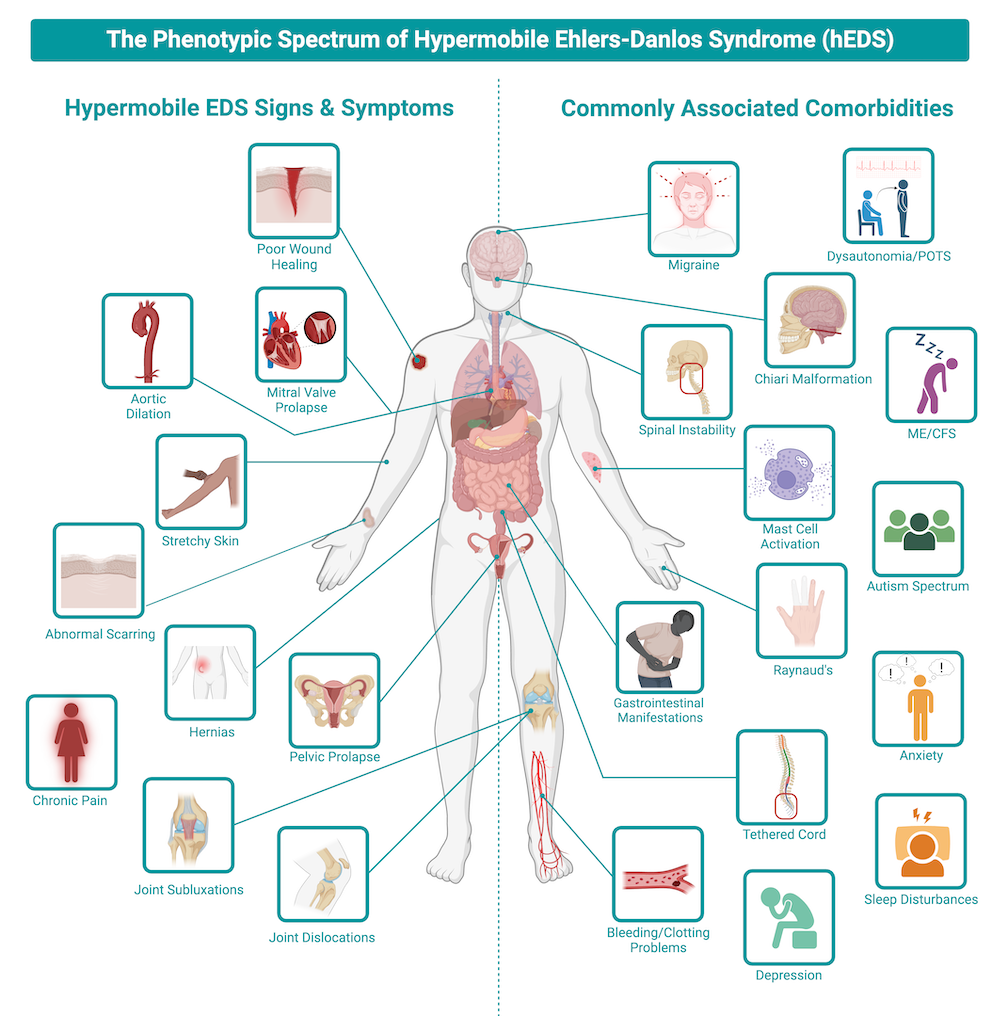

• Many people with hypermobile joints, including those diagnosed with hEDS (hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), a genetic connective tissue disorder causing joint hypermobility, soft tissue fragility, and sometimes systemic symptoms, or HSD (hypermobility spectrum disorder), a broader classification for people with symptomatic joint hypermobility that does not meet full hEDS criteria, can practice yin safely, but the emphasis should be on stability and control rather than pushing to end range (Palmer et al., 2014; Buryk-Iggers et al., 2022).

• Prolonged passive holds change sensory feedback and can temporarily reduce muscle force and activation, but they do not simply “switch the stabilisers off” (Liaghat et al., 2020; Suárez-Iglesias et al., 2019).

• Fascia is mechanosensitive and responds to load and long holds; static stretching can alter fascial stiffness acutely, but tissue remodelling requires repeated loading over time (Ratiu Rathore et al., 2024; Buryk-Iggers et al., 2022).

Here’s the longer answer…

1) Hypermobility and yin: the sensible approach

People with hypermobile joints, including those with hEDS or HSD, are often already near or past end range for many positions. For them, the goal is not more end-range mobility but strength, control, and safe load management (Palmer et al., 2014; Corrado & Ciardi, 2018). Exercise and graded movement are cornerstones of management, and yoga can be part of that toolbox when adapted appropriately.

Practical teacher guidelines

Avoid teaching cues that encourage students to “go deeper,” and invite a sense of tone and connection instead (Palmer et al., 2014).

Offer active alternatives, including engaging surrounding muscles, using props to reduce joint load, or reducing range of motion (Buryk-Iggers et al., 2022).

Pair yin with slow strength work for hips, shoulders, and core to improve joint stability (Liaghat et al., 2020).

The Phenotypic Spectrum of Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS)

2) Passive holds versus active control: what the science says

There has been a lot of online debate about “passive is bad, active is good.” The truth is more nuanced.

What research shows

Static stretching reliably increases range of motion and reduces muscle and fascia stiffness acutely (Suárez-Iglesias et al., 2019; Ratiu Rathore et al., 2024).

Static stretching can produce short-term decreases in strength or muscle activation immediately afterwards, which is reversible (Liaghat et al., 2020; Suárez-Iglesias et al., 2019).

Muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs adapt with sustained input, changing reflex responsiveness; adaptation is not the same as complete shutdown (Corrado & Ciardi, 2018).

In practice, passive holds modify receptor feedback and force output, but whether this is problematic depends on context, the individual, and the teacher’s intent. For a relaxed yin session, some receptor adaptation is part of the intended effect. For hypermobile students, balance with strength or activation work is recommended.

3) Does yin “target the fascia”?

In the introduction, I referred to yin yoga as a “connective-tissue-focused practice,” but this doesn’t mean that the practice magically isolates the fascia which is interwoven and continuous with all the other tissues of the body.

Fascia is a continuous, mechanosensitive connective tissue network that responds to mechanical load (Ratiu Rathore et al., 2024). Static stretching can reduce fascial stiffness acutely, but long-term structural remodelling requires repeated, appropriately dosed mechanical stimuli over time and typically much greater loads than are applied in yoga (Buryk-Iggers et al., 2022).

Teacher guidance

Consistent, progressive loading over weeks or months matters more than a single long hold.

Long passive holds may reduce stiffness acutely, which can feel like “opening,” but lasting change comes from regular practice.

4) Responding to the social media claim

“After about two minutes, the mechanoreceptors in your muscles and fascia, especially the Golgi tendon organs, stop sending fresh information to your brain.”

What research shows: Mechanoreceptors adapt during sustained stretch, but they do not stop sending information. Slowly adapting receptors continue signalling throughout a hold (Corrado & Ciardi, 2018; Liaghat et al., 2020).

“Your proprioceptive awareness fades, and the stabilising muscles go offline.”

Proprioceptive signalling can be altered, and muscle activation can drop temporarily, but “go offline” implies a binary on/off response, which research does not support (Liaghat et al., 2020; Buryk-Iggers et al., 2022).

“What you feel after the ‘release’ point isn’t opening, it’s your nervous system checking out.”

Some of the “release” sensation reflects sensory adaptation and changes in muscle tone. It does not mean nothing is happening; tissue stiffness can decrease, parasympathetic tone can increase, and tension can ease (Suárez-Iglesias et al., 2019).

“Stay at end range for five or six minutes and you overwhelm your sensory systems, creating instability.”

Prolonged stretching affects reflex sensitivity and force production, and in joints that are already unstable, this could raise risk. However, no evidence suggests a single long hold causes lasting instability in a healthy person. Risk is greater in hypermobile joints or when passive holds replace strength training (Palmer et al., 2014; Liaghat et al., 2020).

5) Practical teaching toolbox

For hypermobile students

“Find a comfortable edge, then back off slightly.”

Use props to reduce load on joints.

Offer isometric or lightly active variations within long holds.

Pair yin with strength practice during the week.

Active vs. passive options

Passive: relax with props, focus on breath.

Active: maintain light engagement in surrounding muscles for 30–60 seconds, then release into passive rest. Alternating active and passive work balances stability and sensory input.

Timing guidance

Two to five minutes per pose aligns with research on receptor adaptation and acute increases in range of motion. For more active classes afterward, shorter holds or activation breaks are advisable.

6) Final takeaways

Yin yoga is not inherently unsafe for hypermobile people, but it is advisable to be taught with stability-focused cues and awareness of joint position (Palmer et al., 2014; Buryk-Iggers et al., 2022).

Passive holds alter sensory input and short-term muscle activation but do not create permanent instability (Liaghat et al., 2020; Suárez-Iglesias et al., 2019).

Fascia responds to sustained load and can change acutely, but meaningful remodelling requires consistent practice over time and typically much greater loads than are applied in yoga (Ratiu Rathore et al., 2024).

References:

Buryk-Iggers S., Mittal N., Santa Mina D., Adams S.C., Englesakis M., Rachinsky M., et al. Exercise and rehabilitation in people with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: a systematic review. Arch Rehabil Res Clin Transl, 2022.

Corrado B., Ciardi G. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and rehabilitation: taking stock of evidence-based medicine. J Phys Ther Sci, 2018.

Liaghat B., Jørgensen U., Juul-Kristensen B., Søndergaard J. Heavy shoulder strengthening exercise in people with hypermobility spectrum disorder and long-lasting shoulder symptoms: a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud, 2020.

Palmer S., Bailey S., Barker L., Barney L., Elliott A. The effectiveness of therapeutic exercise for joint hypermobility syndrome: a systematic review. Physiotherapy, 2014.

Ratiu Rathore V., et al. Exploring the therapeutic effects of yoga on spine and related mobility: a systematic review.Complement Ther Clin Pract, 2024.

Suárez-Iglesias D., et al. The effects of yoga compared to active and inactive controls on physical function and health-related quality of life: meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act, 2019.