A clear, evidence-based look at Nadi Shodhana and what it really does for our students.

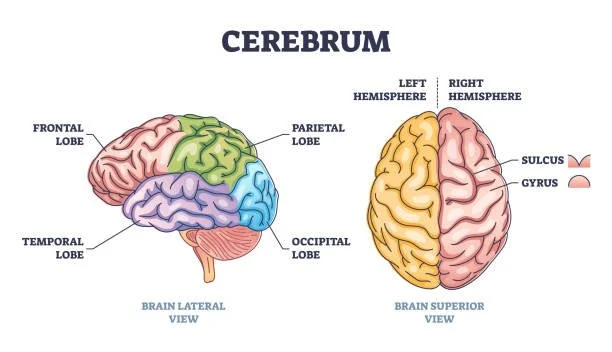

Alternate nostril breathing, Nadi Shodhana, is often described as a way to balance the left and right hemispheres of the brain. It is an appealing idea for teachers who want to explain why this practice feels grounding and settling. However, scientific research tells a more accurate and interesting story.

In this newsletter, we will explore what the hemispheres actually do, why the common left brain logic and right brain creativity narrative is misleading, and what is genuinely occurring during alternate nostril breathing. Most importantly, we will frame this in practical teaching language that supports your students with clarity and confidence.

👉Do the brain hemispheres operate independently?

The short answer is no. The two hemispheres are structurally and functionally connected through a large bundle of fibres called the corpus callosum, which allows continuous communication between them. They work as an integrated whole rather than two separate systems.

There is some hemispheric specialisation. For example, language is usually left dominant. This means that particular aspects of language, such as grammar, vocabulary, and literal meaning, rely more heavily on networks in the left hemisphere (Gazzaniga 1992, Springer and Deutsch 1997). The right hemisphere contributes to tone of voice, emotional nuance, prosody, and the interpretation of metaphor and context (Gazzaniga 1992).

Both hemispheres work together at all times. They do not take turns controlling the brain, and they do not become unbalanced in the way many yoga myths suggest.

👉Does alternate nostril breathing shift hemisphere activity?

There is no strong scientific evidence that alternate nostril breathing selectively activates one hemisphere or balances the two sides. Some early studies suggested that forced dominance of airflow in one nostril might correlate with EEG changes (Stancák and Kuna 1994), but these studies were small, inconsistent, and not well replicated.

Modern neuroscience does not support the idea that nasal airflow patterns meaningfully shift hemispheric activity. Fortunately, we do not need this claim in order to explain the genuine benefits of the practice.

👉What is actually happening during Nadi Shodhana?

1. Autonomic regulation

Slow, controlled breathing increases parasympathetic activity, improves heart rate variability, and reduces physiological stress markers (Pal et al. 2004, Jerath et al. 2006).

2. Reduced stress and increased calm

Research consistently shows reductions in heart rate and blood pressure following slow nasal breathing and pranayama practices (Pal et al. 2004).

3. Improved attention and emotional regulation

Breathing practices that involve sustained focus, patterning, and slow pacing support attention and emotional regulation through prefrontal pathways (Zaccaro et al. 2018).

4. A reliable attentional anchor

The structured sequence of hand movements and breath patterns provides an attentional anchor that helps reduce mental noise and rumination.

These benefits arise from changes in breathing mechanics, attention, and autonomic regulation. None rely on balancing the hemispheres.

👉How to teach this without the myths:

You can confidently teach alternate nostril breathing without referring to left or right brain balancing. Instead, emphasise the evidence-based effects.

• Decreased sympathetic activation

• Increased parasympathetic tone

• Improved focus and present moment awareness

• A steadying effect on heart rate and breath rhythm

• A grounding and settling experience for students

This approach remains accessible, accurate, and empowering, and it supports your students in understanding what is truly happening in their bodies.

👉Accessibility applies to pranayama too:

Accessibility does not only apply to asana. It applies to breathwork too. Many traditional pranayama techniques involve hand positions, sustained breath retention or precise ratios that can feel intimidating or inaccessible for some students. Others may experience anxiety, dizziness or discomfort when asked to control the breath too tightly. Making pranayama feel welcoming, safe and adaptable is an essential part of inclusive teaching.

Research shows that simply bringing attention to the breath can shift autonomic state and support downregulation, even without complex ratios or retentions. Slow, comfortable nasal breathing at a pace that feels sustainable has been linked with reductions in anxiety, improved heart rate variability and enhanced emotional regulation (Zaccaro et al 2018, Balban et al 2023). This means that pranayama does not need to be elaborate to be effective.

For a more accessible variation of Nadi Shodhana, instead of using the fingers to close off each nostril, students can imagine that the breath is flowing through one nostril at a time. They visualise inhaling through the left nostril then exhaling through the right, then inhaling through the right and exhaling through the left. The pathway is created by attention rather than physical manipulation.

The goal is not to perform pranayama perfectly, the goal is to help students explore the breath in a way that feels supportive and sustainable for their unique bodies and nervous systems.

References:

Balban, M. Y., et al. (2023). Breathwork enhances autonomic regulation, mood and stress resilience in adults. Cell Reports Medicine, 4(1), 100895.

Corballis, M. C. (2014). Left brain, right brain, facts and fantasies. PLoS Biology, 12(1), e1001767.

Gazzaniga, M. S. (1992). Nature’s Mind, The Biological Roots of Thinking, Emotions, Sexuality, Language and Intelligence. Basic Books.

Shannahoff-Khalsa, D. S. (2007). Psychophysiological states, the ultradian dynamics of mind-body interactions. International Journal of Neuroscience, 117(2), 149–167.

Telles, S., & Singh, N. (2018). Science of the mind, body and breath, yoga research and public health. International Journal of Yoga, 11(2), 79–80.

Zaccaro, A., et al. (2018). How breath-control can change your life, a systematic review on psychophysiological correlates of slow breathing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 353.